Musée de la mine Epinac

Musée de la Mine et de la Verrerie

Useful Information

| Location: |

Place Charles de Gaulle, 71360 Épinac.

In the Hotel de Ville (town hall) in Epinac. (46.990725, 4.513592) |

| Open: |

Currently closed. [2023] |

| Fee: |

Currently closed. [2023] |

| Classification: |

Coal Mine Coal Mine

Cellar Cellar

|

| Light: |

Electric Light Electric Light

|

| Dimension: | |

| Guided tours: | self guided |

| Photography: | allowed |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: | |

| Address: |

Musée de la Mine, de la Verrerie et du Chemin de Fer, Place de la Mairie, 71360 Épinac, Tel: +33-385-821012.

Mairie d’Épinac, Place Charles de Gaulle, 71360 Épinac, Tel: +33-385-82-10-12. E-mail: |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 1730 | beginning of mining. |

| 1836 | railway from Épinac to Pont-d’Ouche completed. |

| 1855 | steam locomotives delivered. |

| 1872-1876 | Hottinguer mine shaft sunk. |

| 1891 | railway extended to Dijon. |

| 1899 | collieries directed by the engineer Charles Destival. |

| 1910 | power station at the Hottinguer mine sells electricity to the surrounding villages. |

| 1936 | Hottinguer mine closed. |

| 1946 | mines nationalized. |

| 1950 | Moloy mine closed. |

| 1966 | last coal mine, Veuvrottes, closed. |

| 26-NOV-1992 | tour Malakoff at the Hottinguer mine shaft listed as Historic Monument. |

Geology

The Épinac basin contains sandstone and coal shale formed during the Stephanian (307−299 Ma) during the Lower Carboniferous. The coal seams between the sandstone were mined. It is overlain by the Permian of which the Autun oil shale is a part. The sediment layers are tilted in a northeast-southwest orientation.

The Gisement de schiste bitumineux d’Autun (Autun oil shale deposit) is a sedimentary basin containing oil shale of Autunian age (299−282 Ma) in the vicinity of the town of Autun, hence the name. The town gave its name to the geological period, the Autunian, so this is the type locale. The oil shale is obviously mined for the high amount of bitumen, which is extracted by heating.

Description

The Musée de la mine d’Épinac (Épinac Mine Museum) is dedicated to the local coal mines and the Épinac railway and glasswork, which are strongly connected. So there is also a long version of the name, Musée de la Mine, de la Verrerie et du Chemin de Fer (Mine, Glass and Railway Museum). It is located in the village Épinac, in the basement of the town hall, so it is not only a mining museum but also a quite impressive historic cellar.

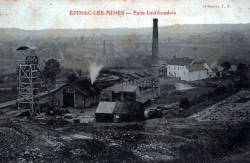

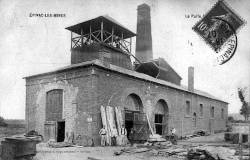

The coal basin of Épinac has an area of about 35 km², between the 18th and 20th century about 70 shafts were sunk in this area. Only ten of them were actually used to extract coal. The mining started with the Count of Clermont-Tonnerre, Lord of Monestoy, who was the first who searched for coal in the 17th century and opened the first pits. However, the beginnings were quite humble. But he founded a glass factory in 1755 which used the coal for glass production and operated successfully until 1934. Underground mining started in 1774 with the Ouche shaft. The miners used candles and oil lamps in the pit and carried the coal in baskets to the surface, where the coal was transported with wheelbarrows.

In a way mining started in 1805 when the first concession was granted. Mining became more professional, but still there was the problem of transporting the coal to the customer. The coal was used locally for producing glass and for lime kilns. The Épinac railway was one of the very first railways built in France. The Compagnie des houillères et du chemin de fer d’Épinac (Coal and railway company of Épinac) was founded in 1829 by the ironmaster and mine owner Samuel Blum, owner of the mining company Samuel Blum et fils. This company purchased four concessions for a total of 7,031 ha and filed a first concession request for a railway from Épinac to Pont-d’Ouche. At the same time, the use of canals was proposed, which was done quite successful in Great Britain at that time. The railway line was built by Samuel Blum and begins at the Curier shaft. It connects several other shafts and ends at the Burgundy Canal at Pont-d’Ouche. It consisted of rolled iron rails of a weight of 13 kg/m posed on blocks out of stone by means of pads with a standard gauge. The trains were not trains in a modern sense pulled by a locomotive. Actually, they used the same technology as in the mine, the track is horizontal, except for two inclined plains. In the horizontal parts the carts were pulled by animals. The first plain had a stationary steam engine with a power of 20 hp which pulled the carts over a distance of 350 m for a slope of 12 ‰. The second inclined plain is towards Pont-d’Ouche at Montceau over a distance of 800 m for a slope of 4.5 ‰. The loaded wagons descended self-propelled by their own weight, and pull empty wagons back up.

The railway was completed 1835, but there were still some problems, and it was finally operational in 1836.

That’s three years later than originally planned, nevertheless was this one of the very first railways built in France, the fourth railway line in France actually.

And it solved the problem to transport coal to consumers.

The first steam powered locomotives were ordered from

Grand Hornu,

Belgium, and delivered in 1855.

Grand Hornu,

Belgium, and delivered in 1855.

Beneath the visit to the museum there is the possibility to take a guided tour of the town, which includes a visit to the Puits Hottinguer (Hottinguer shaft) and a reconstructed miner’s house.

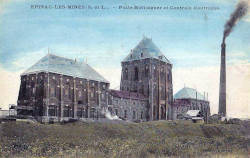

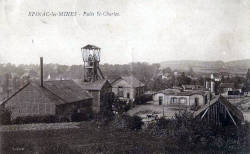

The Hottinguer mine shaft is a

Malakowturm

which was listed as a Historic Monument in 1992.

It was built between 1872 and 1876, and housed a revolutionary atmospheric extraction system, a piston moving in a 558 m high tube.

The shaft was more than 600 m deep, and there was no traditional elevator which allowed this depth.

This renovation of the building and the relocation of the museum to this new building was planned for 2019, but so far the town was not able to finance this.

As far as we know, the museum is currently closed for the relocation, if you plan to go there, please check first at the town hall if it is open.

There is also a walking trail named Circuit des gueules Noires (Trail of the Black Faces), which connects the remains of the ten main shafts of the coal basin.

Malakowturm

which was listed as a Historic Monument in 1992.

It was built between 1872 and 1876, and housed a revolutionary atmospheric extraction system, a piston moving in a 558 m high tube.

The shaft was more than 600 m deep, and there was no traditional elevator which allowed this depth.

This renovation of the building and the relocation of the museum to this new building was planned for 2019, but so far the town was not able to finance this.

As far as we know, the museum is currently closed for the relocation, if you plan to go there, please check first at the town hall if it is open.

There is also a walking trail named Circuit des gueules Noires (Trail of the Black Faces), which connects the remains of the ten main shafts of the coal basin.

- See also

Search DuckDuckGo for "Musée de la mine Epinac"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Musée de la mine Epinac" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark Musée de la mine d’Épinac

Musée de la mine d’Épinac  - Wikipedia (visited: 04-AUG-2023)

- Wikipedia (visited: 04-AUG-2023) Houillères d’Épinac

Houillères d’Épinac  - Wikipedia (visited: 04-AUG-2023)

- Wikipedia (visited: 04-AUG-2023) PUITS HOTTINGUER, UNE CATHÉDRALE INDUSTRIELLE UNIQUE

PUITS HOTTINGUER, UNE CATHÉDRALE INDUSTRIELLE UNIQUE  (visited: 04-AUG-2023)

(visited: 04-AUG-2023) Musée de la Mine, de la Verrerie et du Chemin de Fer

Musée de la Mine, de la Verrerie et du Chemin de Fer  (visited: 04-AUG-2023)

(visited: 04-AUG-2023)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps