Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg

Useful Information

| Location: |

Schlossplatz 1, 35781 Weilburg/Lahn.

(50.485861, 8.260726) |

| Open: |

FEB to MAR Mon-Fri 10-17. APR to OCT Tue-Sun, Hol 10-17. NOV to mid-DEC Mon-Fri 10-17. Last entry 16:30. [2022] |

| Fee: | Adults EUR 3.50, Children (6-16) EUR 2.50, Disabled EUR 2.50, Students EUR 2.50, Families (2+*) EUR 8. Groups (10+): Adults EUR 3, Students EUR 1.50. Groups with guided tour: Adults EUR 4, Students EUR 2. [2022] |

| Classification: |

Mining Museum Mining Museum

Iron Mine Iron Mine

Replica Underground Mine Replica Underground Mine

|

| Light: |

Electric Light Electric Light

|

| Dimension: | L=200 m. |

| Guided tours: | self guided |

| Photography: | allowed |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: | |

| Address: |

Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg, Schlossplatz 1, 35781 Weilburg/Lahn, Tel: +49-6471-379447.

E-mail: |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

Geology

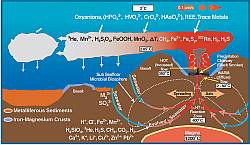

During the Devonian period (400-360 Ma) there was volcanism in this area, through which hydrothermal vents poured iron-rich water at the bottom of the Devonian sea. It formed heavy iron-rich gels on the bottom of the sea from which water-insoluble iron hydroxides, iron oxides and finally red ironstone were formed. The two thickest deposits were formed between the Middle and Upper Devonian, the so-called Grenzlager (boundary deposit), and in the Upper Middle Devonian, the Schalsteinlager (shell deposit). In the Carboniferous the sediments were folded during the Variscan mountain building. In the Lower Carboniferous another phase of volcanism occurred and at the contacts to the magma the Devonian iron ore was transformed into magmatic ironstone. These deposits were later mined. The deposits form two overturned folds, the upper one of which was cut by the surface ablation. Thus, the iron ore was found on the surface and was initially mined in open pits.

In the Lahn-Dill area there are still quite large iron ore deposits with an average iron content of 43%. But underground mining is costly and not worthwhile at current world market prices.

Description

The Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg (Weilburg Mining and City Museum) is located in the center of Weilburg an der Lahn on the Schlossplatz, in an 18th century building once used as the Nassau Chancellery. The permanent exhibition focuses on mining in the Lahn-Dill region. It is one of the oldest iron ore extraction and smelting sites in Germany, but mining ended in the 1970s. After that, a show mine was established below the museum building. The Tiefer Stollen (Long Tunnel) is a 200-meter-long replica of a mining gallery, and displays operational machinery and gives a vivid impression of the former underground working world. On the first floor there are exhibition rooms dedicated to regional iron ore, slate, phosphorite and marble mining as well as clay extraction.

One of the highlights is an inclined elevator, a replica of the Witte-Schacht (Witte shaft) of the Königszug mine near Oberscheld. The shaft was sunk with an inclination of 67°. When the mine was closed in 1955, it had reached a depth of 500 meters. This gave the best possible approach to the ore deposit and saved on roadways and costs compared to a conventional vertical shaft. A 5 ton capacity hoisting vessel and a three-story hoisting cage were moved on two parallel rail lines by a Koepe hoisting machine. Today, the replica of the inclined shaft is the entrance to the mine replica.

Mining began in open pits, with the stability of the rock limiting the possible depth. Once this limit was reached, a new open pit was opened nearby. This created a large number of pits, which can still be seen today in the surrounding forests, they are called Pingen (pits). The ore was smelted on site in a Rennofen (bloomery), a small brick blast furnace. A bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron from oxidic and sulfuric ores. Charcoal from the surrounding forests served as heating material. The resulting sponge iron is called Luppe in Medieval German. Although it still contained considerable amounts of secondary rock and slag, it could already be forged. The locations of the racing furnaces can be identified by the iron slag.

So-called Waldschmieden (forest forges) were the Audenschmiede (1421), the Löhnberger Hütte (1497) and the Christianshütte. At the beginning of the 19th century, there were about 15 blast furnaces in the area. They were known mainly for decorated plates which were used to build ovens. The beginning of industrialization caused the heyday of the mining industry. The use of water power, making the Lahn navigable, the construction of the Weilburg ship tunnel, and the introduction of the railroad were important factors. After the Second World War, however, the mines were no longer competitive and were closed down over time. The last mine in the district, the Fortuna pit, closed in 1983.

- See also

Search DuckDuckGo for "Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Stadt Weilburg an der Lahn

Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Stadt Weilburg an der Lahn  - Wikipedia (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

- Wikipedia (visited: 22-FEB-2026) Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg an der Lahn, official website

Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg an der Lahn, official website  (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

(visited: 22-FEB-2026) Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum

Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum  (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

(visited: 22-FEB-2026) Weilburg, Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum

Weilburg, Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum  (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

(visited: 22-FEB-2026) Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg

Bergbau- und Stadtmuseum Weilburg  (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

(visited: 22-FEB-2026)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps