Donauversickerung

Danube Sink - Danube-Aach-System

Useful Information

| Location: |

Immendingen:

A81 exit Geisingen, B311 direction Tuttlingen, between Geisingen and Immendingen.

Parking lot, panels with explanations.

(47.935239, 8.765747)

Fridingen: A81 exit Geisingen, B311 through Tuttlingen to Neuhausen ob Eck, turn left to Fridingen. Ether walk from the Bergsteig into the valley or from Fridingen along the Danube. (48.011097, 8.933769) |

| Open: |

no restrictions. [2025] |

| Fee: |

free. [2025] |

| Classification: |

Ponor

Malm Ponor

Malm

|

| Dimension: | medium loss of water, 1923-1965 between Kirchenhausen and Möhringen: 6.6 m³/s |

| Guided tours: | self guided |

| Photography: | allowed |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: |

Matthias Selg (2010):

Das Donau Aach-System — Dynamik einer Flussversinkung,

LGRB-Informationen 25, Freiburg i. Br. Juli 2010. S. 7–46, 29 Abb., 10 Tab., 1 Anh., 1 Beil.

pdf

Werner Käss (2021): Das Donau-Aach-System, Geologisches Jahrbuch Reihe A, Band A 165, 2021. 270 Seiten, 138 Abbildungen, 14 Tabellen, 7 Tafeln, ISBN 978-3-510-96862-6. online Werner Käss, Heinz Hötzl (1973): Weitere Untersuchungen im Raum Donauversickerung - Aachquelle (Baden-Württemberg), Steir. Beitr. z. Hydrogeologie, Vol. 25, Seiten 103-116, Graz 1973 pdf |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 1719 | first description of the Danube sink near Immendingen by Breuninger. |

| 1865 | other ponors discovered during the construction of the railroad bridge near Immendingen. |

| 1874 | Schwarzwald-Donau (Black Forest Danube) sinks complete near Immendingen. |

| 1877 | first use of Uranin to mark the water by Knop. |

| 1884 | start of the recording of days with complete disappearing of the Danube. |

| 1911 | Schwarzwald-Donau (Black Forest Danube) sinks complete near Immendingen. |

| 1921 | Schwarzwald-Donau (Black Forest Danube) sinks complete near Immendingen. |

| 1928 | Schwarzwald-Donau (Black Forest Danube) sinks complete near Immendingen. |

| 1943 | Schwarzwald-Donau (Black Forest Danube) sinks complete near Immendingen. |

Description

The Donau (Danube) springs in the Schwarzwald (Black Forest). After leaving the Black Forest the Danube flows to the north-east at the southern rim of the Schwäbische Alb (Swabian Jura) and later the Fränkische Alb (Frankian Jura) towards Regensburg. Here it bends to south-east and leaves Germany near Passau. After many hundred kilometers it flows into the Black Sea.

But from the water which springs at the Danube Spring, only a small part arrives at the Black Sea. Most of it flows into the North Sea. This seems absurd, as the Danube flows into the Black Sea, and the Rhine flows into the North Sea at the opposite end of Europe. The border between their drainage basins is called the European watershed or European drainage divide running through middle and Eastern Europe. So the water of the Danube crosses the watershed. This seems quite strange, but the explanation is rather simple: the upper Danube area is catchment area for two big river systems, as the water is forked and flows into two rivers, the Rhine and the Danube, at the same time. But the catchment area or drainage basin, is defined as an area drained by a (single) stream or another body of water. The limits of a given catchment area are the heights of land - often called drainage divides or watersheds - separating it from neighboring drainage systems. This hydrogeologic water-shed-model is too simple to describe the complex karst hydrogeology of the upper danube.

The sinks are quite inconspicuous, there is no spectacular cave entrance or shaft into which the water falls.

It simply seeps into the gravel in the riverbed over a long distance.

Nevertheless, the Danube sink is a hydrogeologic site of world fame!

The water is not flowing across the water shed, but passes the border underground.

Sinks in the bed of the danube at Immendingen, and later again near Fridingen, swallow a certain amount of water.

The karstified layers of the Malm (late Jurassic) fall to the south and are covered by the much younger sediments of the Süßwassermolasse, the remains of a great lake similar to north Americas Great Lakes.

The biggest swallow holes are at the Brühl between Immendingen and Möhringen, more sinks are downstream near the railroad bridge.

The swallow holes near Fridingen are about 1 km from the town in a loop of the Danube, and are only accessible by foot.

The water flows in the Malm limestone below the overlaying sediments to the

Aachtopf

(Aach spring) in the south.

The speed of the water is from Brühl about 180 m/h and from Fridingen about 100 m/h.

The Aach is a tributary of the Rhine.

Aachtopf

(Aach spring) in the south.

The speed of the water is from Brühl about 180 m/h and from Fridingen about 100 m/h.

The Aach is a tributary of the Rhine.

During the centuries, the loss of water in the Danube increased. The first time the Danube fell completely dry was in 1874. Now the number of days with complete loss of water increased continuously. The maximum was reached 1921 with 309 days! In the days of complete loss, the people talk about Schwarzwald-Donau (Black forest Danube), from the springs to the swallow holes, and the Alb-Donau (Jura Danube). The Jura Danube is "revived" by two tributaries, the Krähenbach and the Elta. While it seems that the amount of water swallowed by the underground cave system increases continually, the days of complete loss are not a sign of higher loss on these days, but of less water in the river. In summer and especially in dry years the amount of water in the danube is smaller than the amount swallowed by the cave system. Increasing precipitation since 1950 reduced the time of complete loss.

The water of the rivers Danube and Aach was always valuable for running mills. And as the Danube and Aachtopf were located in (then) different states, there were soon struggles and fights for the water. The people at the Danube tried to reduce the loss by filling the swallow holes with concrete. Soon the people at the Aach mentioned the decrease of water. At last the case was sentenced at the court in the 1820s.

However, the current situation is that a tunnel has been built between Immendingen and Möhringen. Most of the Danube water is diverted through this tunnel, resulting in full infiltration in Immendingen almost every year. However, as the water flows back into the bed of the Danube one kilometer further on, the Danube does not dry out. In other words, the rather interesting geological situation was “corrected” by technical measures, a massive intervention in the course of the river. Nowadays, however, this seems nonsensical, as the value of the river water is very limited; it is neither needed to power mills nor as industrial or drinking water. On the other hand, the full infiltration is clearly visible even in relatively wet years, which is at least a tourist advantage.

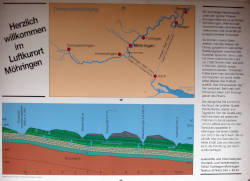

We have listed two places that mark both sink areas. The most interesting and spectacular place can be reached by driving from Möhringen towards Hattingen. At the point where the road leaves the Danube valley and crosses under the railroad line, there is a car park for hikers, which is marked as the Donauversickerung Immendingen. It is also sometimes called Donauversickerung Möhringen. From here it is only a few meters to the Danube, normally you can walk in the dry riverbed of the Danube and cross it on dry feet. If you follow the Danube about 800 m upstream, you will come to the main sink mentioned above. There is a detailed information board at the car park, unfortunately only in German. The sinks in Fridingen are far less spectacular and in most years cannot even be seen with the naked eye, as the water recedes but does not seep away completely. At the southern end of the village, directly on the Danube, there is a car park named Wanderparkplatz Fridingen, where there are also very informative information boards. From here, it is a 1.5 km walk to the sinks. The path is paved in one lane and leads past the sewage treatment plant. Alternatively, you can follow the L277 to the Bergsteig, a path leads downhill from the car park, but you have to walk 1.7 km.

- See also

Danube - Wikipedia

Danube - Wikipedia Google Earth Placemark: Immendingen

Google Earth Placemark: Immendingen OpenStreetMap: Immendingen

OpenStreetMap: Immendingen Google Earth Placemark: Fridingen

Google Earth Placemark: Fridingen OpenStreetMap: Fridingen

OpenStreetMap: Fridingen Danube Sinkhole - Wikipedia (visited: 23-FEB-2025)

Danube Sinkhole - Wikipedia (visited: 23-FEB-2025) Donauversickerung, GeoPark Donaubergland

Donauversickerung, GeoPark Donaubergland  (visited: 23-FEB-2025)

(visited: 23-FEB-2025) Naturphänomen Donauversickerung

Naturphänomen Donauversickerung  (visited: 23-FEB-2025)

(visited: 23-FEB-2025)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps Search

Search