Stillensteinklamm

Useful Information

| Location: |

Struden, 4381 St. Nikola an der Donau.

(48.2480884, 14.8814294) |

| Open: |

no restrictions. [2025] |

| Fee: |

free. [2025] |

| Classification: |

Gorge Gorge

Erosional Cave Erosional Cave

River Cave River Cave

Ponor Ponor

|

| Light: | n/a |

| Dimension: | |

| Guided tours: | self guided |

| Photography: | allowed |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: | |

| Address: | Stillensteinklamm, Panholz 16, 4360 St. Nikola an der Donau, Tel: +43-. |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 1834-1836 | Gießenbach prepared for the Scheiterschwemme (logging) by blasting boulders. |

| 1880 | ÖTK and Verschönerungsverein start building the path. |

| 1894 | ÖTK builds the Gobelwarte |

| 1909 | Donauuferbahn crosses the Gießenbach Valley at Gießenbachmühle via a viaduct with seven arches. |

| 04-MAY-1913 | Foundation of the Strudengau section of the ÖTK. |

| 1915 | Strudengau section of the ÖTK becomes owner of the gorge. |

| 1915 | A storm destroys the paths. |

| 1922 | Start of extension work. |

| 24-JUL-1932 | Opening of the Stillensteinklamm. |

| 1970 | Grein Tourist Association takes over maintenance work in the gorge. |

| 1980 | The bridge, the ascent to the gorge and the "Steinerne Stube" are buried due to carelessness in forestry road construction. |

| 2002 | During the great Danube flood, a flood in the Gießenbach again destroys the bridges and ascent. |

| 2005 | Another flood destroys the paths. |

Description

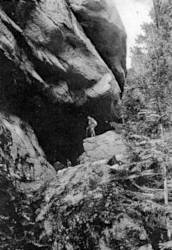

The Stillensteinklamm (Silent Rock Gorge) is hardly comparable to the Alpine gorges in Austria, which are deeply incised and were formed by the meltingwater of the last ice age. The Gießenbach is a northern tributary of the Danube, which is already of considerable size here and flows leisurely towards the Black Sea. The tributary has a slightly steeper gradient, almost 200 metres over the 2.5 km of the gorge, and even a few small rapids, but there are no waterfalls or gradients as steep as in the Alps. The result is more romantic than spectacular. And yet the shapes are comparable, the valley has rocks on both sides made of the local granite. The river has formed vertical rock faces and even overhangs in places, creating small erosional caves. At one point, the path leads through such a cave, which is 3 metres high and 10 metres wide, and runs a good 50 metres along the river.

And yet the most spectacular geological sight is not the erosion forms, but the Gießenbach loosing river. Here, the Giessenbach even flows several times through an underground cave system. One of the caves is up to eight metres high, more than one hundred metres long and has two entrances. This is also the explanation for the name of the gorge, as the Gießenbach stream disappears underground and is therefore silent. However, it should be mentioned that the active river cave is not part of the gorge hike and is only accessible to cave explorers. A wetsuit is also required to enter the cave.

The miller of the Giessenbach mill had died and the miller’s wife lived alone in the mill with her young daughter and a farm labourer. Then the miller’s wife fell ill and no doctor could help her. One day, an old man came and told them about the medicinal herbs that were said to grow deep in the Giessenbach gorge by the waterfall and that they had to be harvested by moonlight. On the next full moon night, the girl set off and after a while she stood in front of a rock face. The medicinal herb had to grow up there! The girl began to climb until a small man, ice-grey and with a bunch of keys on his belt, stood in front of her. "My child, what are you looking for?" the little man asked her gently. The girl told him about her sick mother and the miracle plant. The old man nodded kindly. "You shall have it. Come with me!"

And he pulled her through a gap in the rock face that widened like the halls of a church. Shiny stones sparkled on the walls, strange clusters of flowers hung from waxy bushes, colourful birds fluttered around a throne on which a beautiful woman sat, smiling. The little man led the girl to her. The beautiful woman took the girl by her bruised hands and said in a very gentle voice: "Stay here, my child, stay here!" The girl burst into tears. "Please, let me go back so that I can look for herbs to heal my mother!" Then the woman on the throne waved and the old man led the girl out of the shining hall again.

Bright moonlight shone outside and now the little man broke a strange herb from the rock and placed it in her basket. Then suddenly a thunderclap rumbled through the ravine and the girl fell into a deep sleep. When she woke up again, the sound of the water had disappeared. There was now a stone in the stream, so large that it blocked the river and the gorge, and another one arched over it, gigantic like the roof of a hall. A deathly silence lay over the rocks. The girl fled down the ravine.

As she approached the mill, her mother, who had suddenly recovered, came to meet her. She said anxiously: "My child, where have you been? We’ve been looking for you for three days!" The girl told her what had happened and opened the basket as proof. But the green leaves had turned to pure gold and the drops of water sparkled like shining gemstones! But when they went into the gorge again, they found nothing but the stream, the rocky hall and the deep silence.

This legend of the Silent Stone explains the name of the gorge, which is still referred to as the Giessenbach Gorge at the beginning. However, many details are known from a multitude of legends, the "Mandl" (dwarf?), the white woman, the leaves that turn into precious stones, and that something changes and then everything disappears. Even a kind of time shift, at least a small one of three days. The legend seems to be very well known and can be found with varying degrees of detail.

In the early 19th century, the gorges of the Alps were increasingly used for logging, as this was the only way to transport the valuable timber from the inaccessible Alpine valleys into the valley. Between 1834 and 1836, the Gießenbach stream was also made usable for the "Scheiterschwemme" by blasting boulders. In the 10 years that followed, around 12,000 fathoms of timber were transported. And yet this is somewhat curious here in the lowland north of the Danube. After all there are no inaccessible Alpine valleys here and the expense of blasting and dangerous logging does not really seem to have amortised itself.

Many of the gorges in the Alps were developed from the middle or end of the 19th century, and the Stillenbachklamm was also opened around 1880. There were even two competing organisations, the local groups of the Austrian Tourist Club Vienna (ÖTK) and the Verschönerungsverein. Both built the paths for 20 years, for example the ÖTK built the Gobelwarte in 1894, but it seems that the path was ever completed along its entire length and around 1900 both clubs were dissolved. Eventually, the ÖTK founded the Strudengau section, which still exists today and has owned the gorge since 1915. The beginning was ill-fated - the existing paths were destroyed by a storm in the very first year. The First World War probably also meant that the gorge was not really a high priority, and until 1918 the gorge was only accessible as far as the second waterfall. From 1922 to 1932, the gorge was very comfortably developed and was accordingly popular and well-known. Since 1980 there have been several floods which have destroyed the paths.

We have given the area of the underground flow as the coordinates, which is the centrepiece of the gorge. In fact, it would be possible to reach this area on one of the many hiking trails from the B119, even if there is no car park there. The usual way to visit the gorge is from the B3 on the Danube. There is a large car park below the bridge of the Donauuferbahn railway. From here, follow the well-signposted path upstream past the Gießenbachmühle mill and the Gießenbach power station. The trail is about 2.5 kilometres long and should take about 1.5 hours to walk there and back. Please pay attention to the weather, there is always a risk of flooding when it rains, and there is a weir upstream, which can also be dangerous if it is drained.

Search DuckDuckGo for "Stillensteinklamm"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Stillensteinklamm" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap Stillensteinklamm

Stillensteinklamm  - Wikipedia (visited: 12-AUG-2025)

- Wikipedia (visited: 12-AUG-2025) Stillensteinklamm

Stillensteinklamm  Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps