Catacombe dei Cappuccini

Catacombs of the Capuchins

Useful Information

| Location: |

Palermo, Conventi dei Cappuccini, Piazza Cappuccini.

Piazza Cappuccini, 1, 90129 Palermo PA (38.1119, 13.3392) |

| Open: |

APR to SEP daily 9-13, 15-18. OCT to MAR Mon-Sat 9-13, 15-18, Sun 9-13. [2021] |

| Fee: |

Adults EUR 3. [2021] |

| Classification: |

Catacomb Catacomb

|

| Light: |

Electric Light Electric Light

|

| Dimension: | |

| Guided tours: | self guided |

| Photography: | forbidden |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: |

Dario Piombino-Mascali, Arthur C. Aufderheide, Melissa Johnson-Williams, Albert R. Zink (2009):

The Salafia method rediscovered,

Virchows Archiv. 454 (3): 355–357. PMID 19205728. S2CID 26848891.

pdf

DOI

|

| Address: |

Catacombe dei Cappuccini, Piazza Cappuccini 1, Palermo, Sicily, Tel: +39-0915-85172.

E-mail: |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 1534 | Capuchin friars established at the church of Santa Maria della Pace (Lady of Peace). |

| 1597 | old cemetery full, begin of excavation of catacombs. |

| 1599 | Capuchin monks discover the preservative effect of their catacombs. |

| 1623 | monastery rebuilt. |

| 1871 | Brother Riccardo was the last friar buried here. |

| 1880 | catacombs officially closed but tourists continued to visit. |

| 1920 | last person buried here. |

| 1940s, | hit by Allied bombs and part of the mummies destroyed. |

| 1957 | Giuseppe Tommasi, prince of Lampedusa and author of The Leopard buried here. |

| 2007 | Sicily Mummy Project created to study the mummies and to create profiles on those who were mummified. |

| 2011 | census made by EURAC. |

Description

The Catacombe dei Cappuccini (Capuchin Catacombs) at Palermo are world famous, because of their mummifying effect. It was first discovered in 1599 when the monks built a new burial place below the church because the original cemetery was full. The first one to be buried was the recently-deceased Fra Silvestro of Gubbio. It is not exactly clear if they intentionally mummified him to store him in the catacombs, or if this effect was unintended. Nevertheless they started to relocate their dead from the old cemetery.

The catacombs were intended only for deceased friars, but soon, when the effect became known, many inhabitants of Palermo, especially the upper class, demanded to be buried here. They believed the mummification was an act of god. It became a status symbol to be entombed in the Capuchin catacombs. Over the centuries many thousand persons were buried here, some talk of 4,000, others of 8,000 bodies. According to a census made by EURAC in 2011 there are 1,252 mummies and about 8,000 corpses. Some were not preserved perfectly, others were destroyed during World War II, when the monastery was hit by Allied bombs, so at the moment the catacombs contain about 1,200 bodies.

The habit to bury their dead in the catacombs was abandoned first by the friars, they stopped in 1871. The locals still wanted to be buried here, until this was finally discontinued in 1920. Only one more person was buried here afterwards, Giuseppe Tommasi, prince of Lampedusa and author of The Leopard. You probably remember the movie by Luchino Visconti with Burt Lancaster from 1963. He was buried in the catacombs in 1957.

Actually there is no special property of the location which causes the mummification, the place was simply dry and so the bodies did not decay but dry. The monks washed some of the bodies with vinegar, to support the process. Some bodies were embalmed, but very few. This habit started in the early 20th century and was performed by Professor Alfredo Salafia. His process was long forgotten but was reconstructed by scientists in 2009. He used formalin to kill bacteria, alcohol to dry the body, glycerin to keep it from drying too much, salicylic acid to kill fungi, zinc sulfate and zinc chloride to give the body rigidity.

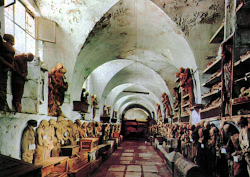

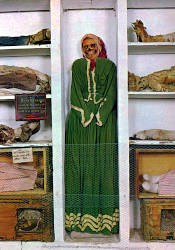

Today the catacombs form a series of five corridors, each dedicated to a certain group of people. One is for men, one for women, one for famous people, one for monks and one for priests. Some bodies are set in poses, many wear their finest garment, some are hanging on the wall in upright position. Some were regularly visited by their descendants and kept in a presentable state.

Today the catacombs have become a tourist attraction, one of the macabre kind. Obviously it is not really a tourist site, and it is definitely not a museum or a theme park. If you visit the site be aware that tis is a graveyard inside a church and behave accordingly, which includes wearing appropriate clothes. Photography is forbidden for this reason and iron grills have been installed to prevent tourists tampering or posing with the corpses. The pictures on this page are quite old and were taken when it was still allowed, some 50 years ago. And while catacombs are considered underground, this site is actually not underground, its just a basement.

"I wanted to visit, immediately, this sinister collection of the deceased".

At the door of a small, modest-looking convent, an old Capuchin, in a brown robe, receives me and he precedes me without saying a word, knowing well what strangers who come to this place want to see.

We cross a poor chapel, and slowly descend a wide stone staircase. And suddenly I saw before us an immense gallery, wide and high, the walls of which carry a whole crowd of skeletons dressed in a bizarre and grotesque fashion. Some are hanged in the air side by side, others lying on five stone tablets, superimposed from the floor to the ceiling. A line of words is standing on the ground, a compact line, whose hideous heads seem to speak. Some are eaten away by hideous vegetation which further deforms the jaws and bones, others have kept their hair, others a bit of mustache, others a lock of beard. These look up with their empty eyes, those below; here are some who seem to laugh horribly, there are some who are twisted by pain, all of them seem terrified by a superhuman terror. And they are dressed, these dead, these poor hideous and ridiculous dead, dressed by their family who pulled them from the coffin to make them take place in this frightening assembly. Almost all of them have some sort of black robe, the hood of which is sometimes pulled back over the head. But there are some that we wanted to dress more sumptuously; and the wretched skeleton, wearing an embroidered Greek cap and wrapped in a rich annuitant’s dressing gown, stretched out on his back, seems to be sleeping in a terrifying and comical sleep. dressed by their family who pulled them from the coffin to make them take their place in this frightening assembly. Almost all of them have some sort of black robe, the hood of which is sometimes pulled back over the head. But there are some that we wanted to dress more sumptuously; and the wretched skeleton, wearing a Greek cap with embroidery and wrapped in a rich annuitant’s dressing gown, stretched out on his back, seems to be sleeping in a terrifying and comical sleep. dressed by their family who pulled them from the coffin to make them take their place in this frightening assembly. Almost all of them have some sort of black robe, the hood of which is sometimes pulled back over the head. But there are some that we wanted to dress more sumptuously; and the wretched skeleton, wearing an embroidered Greek cap and wrapped in a rich annuitant’s dressing gown, stretched out on his back, seems to be sleeping in a terrifying and comical sleep.

A blind man’s placard, hung around their neck, bears their name and the date of their death. These dates send shivers through the bones. It reads: 1880, 1881, 1882.

So here’s a man, what was a man eight years ago? It lived, laughed, talked, ate, drank, was full of joy and hope. And here it is! In front of this double line of unnameable beings, coffins and crates are piled up, luxurious black wooden coffins, with copper ornaments and small tiles to see inside. One would think that they are trunks, suitcases of savages bought in some bazaar by those who go on the great journey, as was once said.

But subterranean galleries open to the right and left, indefinitely extending this immense underground cemetery.

Here are the women, even more burlesque than the men, because they have been adorned with coquetry. The heads look at you, tight in lace caps and ribbons, snow-white around those black faces, rotten, eaten away by the strange work of the earth. Hands like rootstree cut, come out of the sleeves of the new dress, and the stockings seem empty which enclose the bones of the legs. Sometimes the dead man only wears shoes, big, big shoes for those poor dry feet.

Here are the young girls, the hideous young girls, in their white finery, wearing around their foreheads a metal crown, a symbol of innocence. They look like old women, very old, they grimace so much. They are sixteen, eighteen, twenty. How awful!

May we arrive in a gallery full of little glass coffins - these are the children. the barely hard bones could not resist. And we do not really know what we see, they are so distorted, crushed and dreadful, the miserable kids. But tears come to your eyes, for the mothers have dressed them in the little costumes they wore on the last days of their lives. And they come to see them again, their children!

Often, next to the corpse, hangs a photograph showing it as it was, and nothing is more striking, more terrifying than this contrast, than this coming together, than the ideas awakened in us by this comparison.

We cross a darker, lower gallery, which seems to be reserved for the poor. In a dark corner, there are about twenty of them together, suspended under a skylight, which gives them the outside air in great sudden breaths. They are dressed in a sort of black canvas tied at the feet and at the neck, and leaning over each other. We wanted them to shiver, that they wanted to save themselves, that they shout "help!" One would think the drowned crew of some ship, still beaten by the wind, wrapped in the brown and tarred canvas that the sailors wear in storms, and still shaken by the terror of the last moment when the sea has seized them.

Here is the district of the loans. A large gallery of honor! At first glance, they seem more terrible to see than the others, thus covered with their black, red and purple sacred ornaments.

But looking at them one after the other, a nervous and irresistible laugh seizes you in front of their bizarre and sinisterly comical attitudes. Here are some that are charming; here are some who pray. We lifted their heads and crossed their hands. They are wearing the bar of the officiant who, placed at the top of their emaciated forehead, sometimes leans over the ear in a playful way, sometimes falls to their noses. It is the carnival of death, made more burlesque by the golden richness of the priestly costumes.

Every now and then, it seems, a head rolls down the neck ties that have been gnawed by the mice. Thousands of mice live in this human mass grave.

I am shown a man who died in 1882. A few months earlier, gay and in good health, he had come to choose his place, accompanied by a friend: "I will be there", he would say and laugh.

The friend comes back alone now and stares for hours on end at the motionless skeleton, standing in the place indicated.

On certain holidays, the Capuchin catacombs are open to the crowd. A drunkard fell asleep once there and awoke in the middle of the night. He called, screamed, terrified, ran all around, trying to flee. But no one heard him. It was found in the morning, so clinging to the bars of the entrance gate that it took a long effort to untie it.

He was crazy.

Since that day, a big bell has been hung near the door.

Guy de Maupassant

- See also

Search DuckDuckGo for "Catacombe dei Cappuccini"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Catacombe dei Cappuccini" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark Capuchin catacombs of Palermo - Wikipedia (visited: 26-JUL-2021)

Capuchin catacombs of Palermo - Wikipedia (visited: 26-JUL-2021) The Capuchin Catacombs, official website (visited: 26-JUL-2021)

The Capuchin Catacombs, official website (visited: 26-JUL-2021) Capuchin Monastery Catacombs - Atlas Obscura (visited: 26-JUL-2021)

Capuchin Monastery Catacombs - Atlas Obscura (visited: 26-JUL-2021) Catacombe dei Cappuccini (Catacombs of the Capuchins) - Palermo, Sicily, Italy (visited: 26-JUL-2021)

Catacombe dei Cappuccini (Catacombs of the Capuchins) - Palermo, Sicily, Italy (visited: 26-JUL-2021) Catacombe dei Cappuccini

Catacombe dei Cappuccini  (visited: 26-JUL-2021)

(visited: 26-JUL-2021) Sicilian Mummies Bring Centuries to Life (visited: 26-JUL-2021)

Sicilian Mummies Bring Centuries to Life (visited: 26-JUL-2021)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps