Musée des Egouts de Paris

Useful Information

| Location: |

Pont de l’Alma, rive gauche, Face au 93 quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris.

Metro station Alma-Marceau (Line 9), Invalides (Lines 8 and 13). Cross Pont de l’Alma bridge, turn left into Quai d’Orsay, large blue sign. (48.862602, 2.302656) |

| Open: |

16-JAN to DEC Tue-Sun 10-17, last entry 16. Closed 01-MAY, 25-DEC. [2023] |

| Fee: |

Adults EUR 9, Children (0-18) free, Europeans (18-26) free, Seniors EUR 7, Disabled free, Unemployed free. [2023] |

| Classification: |

Sewage System Sewage System

|

| Light: |

Electric Light Electric Light

|

| Dimension: | L=2,400,000 m, T=13 °C. |

| Guided tours: |

D=60 min, L=500 m, VR=3 m.

Audioguide

V=95,000/a [2007] V=80,000/a [2017] |

| Photography: | allowed |

| Accessibility: | yes |

| Bibliography: |

Donald Reid (1993):

Paris Sewers and Sewermen: Realities and Representations

Harvard University Press; Reprint edition (March 1, 1993), ISBN-10: 0674654633, ISBN-13: 978-0674654631

Victor Hugo (1862): Les Misérables Part 5, Jean Valjean; Book II, The Intestine of the Leviathan, ch.1, The Land Impoverished by the Sea. H. L. Humes (1958): The Underground City |

| Address: |

Musée des Égouts de Paris, Pont de l’Alma, rive gauche, Face au 93 quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris, Tel: 47-051029, Tel: +33-153-682781.

E-mail: |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 1200 | first paved streets with drainage channel in the middle. |

| 1348-1349 | a plague wipes out many citizens, caused by unsanitary conditions. |

| 1370 | Hugues Aubriot builds a 300 m stone-walled sewer under rue Montmartre. |

| 1600s | additional sewer construction in certain areas by Louis XIV. |

| early 1800s | Napoleon ordered the construction of a network of sewer tunnels totaling 30 km. |

| 1832 | major outbreak of cholera. |

| 1850 | engineer Eugène Belgrand hired to design a complete system for water supply and waste removal. |

| 1867 | first public tours offered for the Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair). |

| 1878 | sewer system reaches a length of 600 km. |

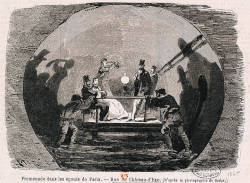

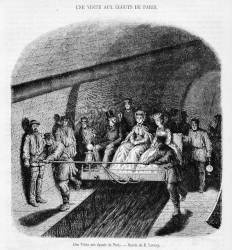

| 1892 | visitors ride through the sewers in a a boat and a wagon pushed by four sewer workers in white uniforms. |

| 1894 | law enacted which requires all waste to be sent to the sewers. |

| 1906 | push-wagons replaced by electric locomotive-drawn trains. |

| 1975 | wagon tours abandoned, museum opened to the public with a 500 m underground walking tour. |

| 1989 | museum renovated. |

| 2018 | sewer museum closed for a complete renovation of its route. |

| 23-OCT-2021 | museum reopened. |

Description

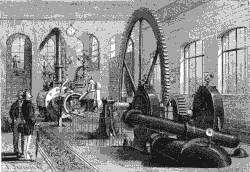

The Musée des Égouts de Paris (Paris Sewer Museum) is not simply about the sewers, it is located inside the sewers. 500 m of the sewers has been turned into a museum. Exhibits show the machinery and techniques used to dredge the sand and solid waste from the channels. The modern computerized monitoring system is also explained.

Medieval cities in Europe used the streets for waste water, the fekals of the night were thrown out of the window on the street. If someone was hit, this was considered funny. Later channels were built along the street, which reduced the dirt on the road itself. Nevertheless, there was still horse dung on the road, from the carts and coaches. The situation was dirty, smelly and unhygienic. With growing cities, diseases were unavoidable. Some rulers or municipalities were aware of the problem and tried to solve it. For example, Napoleon ordered the construction of a network of sewer tunnels totaling 30 km in the early 1800s. Nevertheless, most cities started to build sewers in the second half of the 19th century.

In Paris, a major outbreak of cholera in 1832 was for the first time considered a result of unhygienic waste water treatment. It nevertheless took decades until finally the engineer Eugène Belgrand was hired in 1850. He designed a complete system for water supply and waste removal. It took an enormous work of many years, until finally in 1894 a law was enacted that required all waste to be sent to the sewers. The French call this the transition from tout à la rue (all in the street) to tout à l’égout (all in the sewer). The sewer system grew year by year and street by street for half a century.

The sewer tunnels of Paris are huge, about the size of a subway tunnel, at least the central collectors. In most cases, they are wide enough and deep enough for a boat, with broad, paved walkways on both sides, high enough for most people to walk upright. Along the ceiling run various pipes, like fresh water, telecommunication cables, and pneumatic tubes.

The enormous size and complexity of the sewer system makes it a true labyrinth. To help the workers, each corner has street signs that mirror the ones on the surface. Wide sewer tunnels correspond with wide boulevards on the surface, smaller sewers with smaller streets.

The museum has a long history, almost as long as the sewer system itself. In a way, it was founded in 1867, in the year of the Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair). Organized sewer visits were offered and were met with immense public success. The sewers were new, the plans had been published in newspapers, but very few except the workers had actually seen them, so people were curious. The sewers became a propaganda tool intended to promote the modernity of the capital. Crowned heads, bourgeois in search of thrills and engineers on a study mission frequented the tours. The visits started at Châtelet via Concorde, Sébastopol, Rivoli and Asnières collectors and ended at Madeleine. The tours were guided by the sewer workers and were done by boat and special trains. In the first section the women were sitting on the boat, and the men followed on foot. The second part was done by wagonette, a wagon with comfortable seats, pushed by four sewer-men in white outfits. Soon the number of visitors increased. Eugene Belgrand, the director of the Waters and Sewers of Paris, describes that he had nine elegant small wagons built, which seated 10 persons.

Like a mystic labyrinth, the sewers became a source of inspiration and fantasy for artists, royalty, and people from all over the world. The sewers of Paris have provided material for many famous writers during the centuries. One of the most famous is probably Victor Hugo, who spent about 50 pages of Les Misérables describing the sewers. He did not visit them himself, the description was based on information he received from his friend Emmanuel Bruneseau. He was the sewer inspector Napoleon commissioned to explore the tunnels and create an exhaustive map of the sewers as they existed in the early 1800s. The sewers are also mentioned in Phantom of the Opera and in Umberto Eco’s novel Foucault’s Pendulum.

When the first metro line was built, the route had to be changed. In 1906, the wagons were electrified, and became small trains which seated 100 visitors and used the passage in both directions. The corridors were spacious, lit and almost odourless, so one wonders why they were nevertheless so popular. The route was equipped with educational signs for important infrastructure. During World War II, the sewers were closed to visitors. They were considered of strategic importance, and parts were transformed into shelters. Of course, the resistance also used the tunnels. In 1946 the tours were reopened, staring at the Place de la Concorde. The train rides were finally discontinued in 1975, when they were replaced by a museum.

The sewer museum, telling the history of the sewers and its various tools and machines, was set up in 1975. Located at the working Alma plant, it included a 500 m underground walking tour. When the Seine has high water, the museum is flooded and therefore closed. The museum is very popular and has 100,000 visitors per year. It was renovated for the first time in 1989, and again from 2018 to 2021 for a major refurbishment. The 2-million-Euro project was managed by the architectural firm Frenak and Jullien, and included the creation of access for disabled people. The former entrance was replaced ny a new reception pavilion.

Quite interesting is the Eugène Belgrand Gallery. It is named after engineer Eugène Belgrand, Director of the Paris water and sewer service. He was in charge of the development of a water supply and a sewer system, and is the father of the sewers. He invented numerous technical details, like cleaning tools, various cleaning balls, and valves. He was also the deputy of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, who modernized numerous aspects of the city at this time.

- See also

Search DuckDuckGo for "Musée des Egouts de Paris"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Musée des Egouts de Paris" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap Paris Sewer Museum - Wikipedia (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

Paris Sewer Museum - Wikipedia (visited: 22-FEB-2026) Paris Sewers Museum, official website (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

Paris Sewers Museum, official website (visited: 22-FEB-2026) Bad Taste Tour: The Sewers of Paris (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

Bad Taste Tour: The Sewers of Paris (visited: 22-FEB-2026) European Sewer Safari (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

European Sewer Safari (visited: 22-FEB-2026) Musee des Egouts (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

Musee des Egouts (visited: 22-FEB-2026)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps