Cueva de Montesinos

Useful Information

| Location: |

C-30, 5, 02611 Ossa de Montiel, Albacete.

(38.939047, -2.809922) |

| Open: |

All year daily 9:30-14, 16-20:30. Only with reservation. [2023] |

| Fee: |

Adults EUR 5. [2023] |

| Classification: |

Karst Cave Karst Cave

|

| Light: | bring torch |

| Dimension: | L=59 m, VR=45 m, T=14 ºC. |

| Guided tours: | D=1.5 h. |

| Photography: | allowed |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: |

Miguel de Cervantes (1615):

El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha,

Part II, Chabper 22-23.

online

|

| Address: |

Cueva de Montesinos Turismo Activo, C-30 s/n, 02611 Ossa de Montiel, Albacete, Tel: +34-684-02-93-44.

E-mail: Oficina de Turismo de Ossa de Montiel, Ctra. de Las Lagunas, km. 0’500, Tel: +34-967-37-76-70. E-mail: |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 1578 | first written mention in the never printed Relaciones de Felipe II. |

| 1615 | setting in the second part of Don Quixote de la Mancha. |

| 1895 | Charles Bogue Luffman, in his book A Vagabond in Spain, spoke of the cave as "a large chamber that opens to the left as one descends". |

| 20-JUN-2017 | declared an Bien de Interés Cultural (BIC) (Asset of Cultural Interest). |

Description

Cueva de Montesinos (Cave of Montesinos) is a karst cave which is almost devoid of speleothems. There are only a few small soda straws. The cave is only 59 m long but has a total depth of 45 m. The entrance is located on the plain, a collapse with huge boulders, a stone staircase leads down to the entrance portal which is today called Portal, stating the obvious. It was known as Los Arrieros (The Muleteers) because it was their shelter from bad weather. A short passage or vestibule with numerous blocks from the collapse descends to a big chamber, which is called La Gran Sala (The Great Hall). This chamber is 18 m long and up to 5 m high. The floor is steep and the blocks originally required some climbing, today there is a staircase and a beaten path. The single passage descends continually to the end, there are no notable side passages, except for a rather small side passage right below the entrance. At the far end, the lowest part reaches the groundwater, with several cave lakes, which are full of calcite crystals.

The cave was visited by Prehistoric people, Iberians and Romans. Flint knives, flint arrows (microliths) and pieces of polished axes were found in the cave. But it is famous for its important role in the book Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. Of course, the cave is not actually described in the book, its unclear if the author ever visited it. But today most people visit the cave because of the famous name. And the description how he is lowered into the cave is quite impressive.

The cave was first mentioned in a description of the country which was ordered by Felipe II in 1574. The next time it was used by Cervantes in Don Quixote de La Mancha Part II in chapter 22. While there is an impressive description how Don Quixote was lowered into a daylight shaft on a rope, the cave is actually no daylight shaft. So this part is obviously already wrong, but after being descended 20 m into the shaft he saw a side passage on the right side. This makes no sense at all, as it depends on his orientation only, while hanging on a rope, if this passage is to the right, left, front or back. Anyone who has been lowered on a rope knows that you are constantly spinning. Nevertheless, Charles Bogue Luffman corrected the description in his book A Vagabond in Spain from 1895. He describes it as "a large chamber that opens to the left as one descends." August Jaccaci then corrects Luffman and says "...is on the right, as in the story." A weird discussion, as he also states that "Cervantes had not seen the cave, but only heard about it." He published his book An American in La Mancha in the footsteps of Don Quixote in 1897. And another chapter was dedicated to the cave by Azorin (pseudonym of José Martínez Ruiz) in his book The route of Don Quixote in 1905.

Its a strange story about people being enchanted in the cave for hundreds of years, which is told in Chapter 23, after Don Quixote recuperated from his strenuous sleep. While we have cited below the actual description of the cave, for this story you should read the book which is available as ebook for free. Just a few comments on the background. Don Quixote tells that he met Montesinos, who told him that Merlin had enchanted them. The name Montesinos appears various times in the book, as he is the great role model of Don Quixote, a knight who represents the idealized knighthood. Montesinos it is the name of a famous Spanish knight, who is mentioned in numerous Spanish ballads dealing with Carolingian legends. The story goes that Durandarte is wounded deadly in battle, is found by his cousin Montesinos, tells him to bring his heart to Belerma, who he had served seven years, but could not win her favor. Montesinos cuts out his heart, buries the body and brings the heart to Belerma. Even at that time this was probably not a sane behaviour. It seems Cervantes found the idea distasteful but funny, so his Montesinos explains that he put salt on the heart because it started to smell bad.

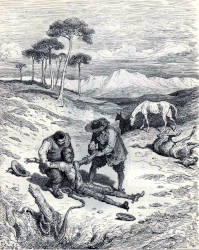

When he had said this and finished the tying (which was not over the armour but only over the doublet) Don Quixote observed, “It was careless of us not to have provided ourselves with a small cattle-bell to be tied on the rope close to me, the sound of which would show that I was still descending and alive; but as that is out of the question now, in God’s hand be it to guide me;” and forthwith he fell on his knees and in a low voice offered up a prayer to heaven, imploring God to aid him and

grant him success in this to all appearance perilous and untried adventure, and then exclaimed aloud, “O mistress of my actions and movements, illustrious and peerless Dulcinea del Toboso, if so be the prayers and supplications of this fortunate lover can reach thy ears, by thy incomparable beauty I entreat thee to listen to them, for they but ask thee not to refuse me thy favour and protection now that I stand in such need of them.

I am about to precipitate, to sink, to plunge myself into the abyss that is here before me, only to let the world know that while thou dost favour me there is no impossibility I will not attempt and accomplish.” With these words he approached the cavern, and perceived that it was impossible to let himself down or effect an entrance except by sheer force or cleaving a passage; so drawing his sword he began to demolish and cut away the brambles at the mouth of the cave, at the noise of which a

vast multitude of crows and choughs flew out of it so thick and so fast that they knocked Don Quixote down; and if he had been as much of a believer in augury as he was a Catholic Christian he would have taken it as a bad omen and declined to bury himself in such a place.

He got up, however, and as there came no more crows, or night-birds like the bats that flew out at the same time with the crows, the cousin and Sancho giving him rope, he lowered himself into the depths of the dread cavern; and as he entered it Sancho sent his blessing after him, making a thousand crosses over him and saying, “God, and the Peña de Francia, and the Trinity of Gaeta guide thee, flower and cream of knights-errant.

There thou goest, thou dare-devil of the earth, heart of steel, arm of brass; once more, God guide thee and send thee back safe, sound, and unhurt to the light of this world thou art leaving to bury thyself in the darkness thou art seeking there;” and the cousin offered up almost the same prayers and supplications.

Don Quixote kept calling to them to give him rope and more rope, and they gave it out little by little, and by the time the calls, which came out of the cave as out of a pipe, ceased to be heard they had let down the hundred fathoms of rope.

They were inclined to pull Don Quixote up again, as they could give him no more rope; however, they waited about half an hour, at the end of which time they began to gather in the rope again with great ease and without feeling any weight, which made them fancy Don Quixote was remaining below; and persuaded that it was so, Sancho wept bitterly, and hauled away in great haste in order to settle the question.

When, however, they had come to, as it seemed, rather more than eighty fathoms they felt a weight, at which they were greatly delighted; and at last, at ten fathoms more, they saw Don Quixote distinctly, and Sancho called out to him, saying, “Welcome back, señor, for we had begun to think you were going to stop there to found a family.” But Don Quixote answered not a word, and drawing him out entirely they perceived he had his eyes shut and every appearance of being fast asleep.

They stretched him on the ground and untied him, but still he did not awake; however, they rolled him back and forwards and shook and pulled him about, so that after some time he came to himself, stretching himself just as if he were waking up from a deep and sound sleep, and looking about him he said, “God forgive you, friends; ye have taken me away from the sweetest and most delightful existence and spectacle that ever human being enjoyed or beheld.

Now indeed do I know that all the pleasures of this life pass away like a shadow and a dream, or fade like the flower of the field.

O ill-fated Montesinos! O sore-wounded Durandarte! O unhappy Belerma! O tearful Guadiana, and ye O hapless daughters of Ruidera who show in your waves the tears that flowed from your beauteous eyes!”

The cousin and Sancho Panza listened with deep attention to the words of Don Quixote, who uttered them as though with immense pain he drew them up from his very bowels.

They begged of him to explain himself, and tell them what he had seen in that hell down there.

“Hell do you call it?” said Don Quixote; “call it by no such name, for it does not deserve it, as ye shall soon see.”

...

“A matter of some twelve or fourteen times a man’s height down in this pit, on the right-hand side, there is a recess or space, roomy enough to contain a large cart with its mules. A little light reaches it through some chinks or crevices, communicating with it and open to the surface of the earth. This recess or space I perceived when I was already growing weary and disgusted at finding myself hanging suspended by the rope, travelling downwards into that dark region without any certainty or

knowledge of where I was going, so I resolved to enter it and rest myself for a while. I called out, telling you not to let out more rope until I bade you, but you cannot have heard me. I then gathered in the rope you were sending me, and making a coil or pile of it I seated myself upon it, ruminating and considering what I was to do to lower myself to the bottom, having no one to hold me up; and as I was thus deep in thought and perplexity, suddenly and without provocation a profound sleep fell

upon me..."

Miguel de Cervantes (1615): Don Quixote Part II, Chapter XXII and XXIII.

The cave tours are operated by the Cueva de Montesinos Turismo Activo, a sort of outdoor operator which offers various activities, including kayaking and guided walks. The guided tours into the cave are one of their tours. To visit the cave it is necessary to book such a cave tour on their website. The normal tour is just a cave visit with some explanations about the literature background. They also offer dramatic guided tours of Cueva de Montesinos, where actors replay the scene from Don Quixote. The cave is gated, so it is not possible to visit it without a tour. As it has no light helmets with headlamp are provided. Fortunately it’s not necessary to abseil, as there is definitely no shaft.

Search DuckDuckGo for "Cueva de Montesinos"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Cueva de Montesinos" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark Cueva de Montesinos

Cueva de Montesinos  - Wikipedia (visited: 10-APR-2023)

- Wikipedia (visited: 10-APR-2023) Cueva de Montesinos, official website

Cueva de Montesinos, official website  Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps