The Cave Of Bellamar

By General Frederico F. Gavada

from: Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol 41, Issue 246, November 1870, pp. 826-834, Harper & Bros. New York.

THE Cave of Bellamar, although discovered but a few years since, already enjoys a world-wide reputation. At the present day no visitor to Cuba fails to repair to that wondrous subterranean palace, unrivalled, perhaps, in the grandeur of its stalactitic masses and the exquisite detail of its sparry decorations. Easy of access from Havana by railway, and commodiously and safely prepared for the reception of visitors, it fully repays one for a day’s absence from the busy scenes of the capital.

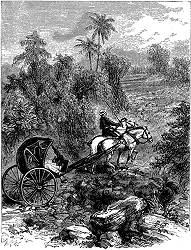

About a mile from the bridge of Bailen, on the south side of the city of Matanzas, there is a group of pretty villas designated by the name of Bellamar - a favorite place of resort in the hot season for sea-bathing. Not far from there is the famous cavern, which borrows its name from this picturesque hamlet. At a short distance beyond Bellamar you turn your back upon the foamy beach, and, following a tortuous road of reddish earth, thickly strewn with fragments of calcareous rock, you ascend a steep and rugged hill, on the summit of which is the entrance to the cave.

On the 17th of April, 1861, some laborers were at work on this hill extracting limestone for a kiln, which still stands on the premises. One of these laborers, in forcing a crow-bar into the interstices of the loose rock, suddenly felt it slip through his hands and disappear, as if by magic, into the earth. Upon examination it was discovered that the crow-bar had slid through a fissure into a sort of well-like cavity. This natural well was very deep and dark. In a few days the opening made by the crow-bar was widened sufficiently to admit the body of a man. It needed no little boldness to venture into the yawning abyss of this cavity at the end of a rope. Mr. Santos Parga, owner of the premises, having been informed of the mysterious disappearance of the crow-bar, upon gazing down into this opening, surmised that the most valuable portion of his property was not on his lands, but under them. Being a man of nerve and intrepidity, he resolved to unravel for himself the secrets of this remarkable cavern. Upon being lowered through the perilous aperture he found himself, torch in hand, descending into a vast and magnificent temple, whose pillars were of glittering crystal, and whose lofty dome was formed of fantastic arches that sparkled as if coated with frosted silver.

Parga was not able to explore his wonderful subterranean domain very far, owing to the dangers which threatened him at every step. There were deep gullies which he could not cross, and steep precipices down which it would have been madness to attempt a descent. It was not without considerable labor that he, with a few companions, succeeded after several days in penetrating into some of the main avenues.

At present the visitor finds every thing very conveniently arranged for the descent. A comfortable pavilion has been constructed over the entrance, rendered accessible by the improvement of the roads to vehicles from the city.

Led by a guide, who provides us with a lantern or a torch made of long wax-candles twisted together, we descend by a stairway into the cave. This stairway is furnished with a hand-rail, and is supported by an artificial wall. We descend some twenty or thirty steps to an eminence within, around which a railing has been placed that we may safely approach the verge of the precipice, and gaze into the frightful abyss below. Here also we may divest ourselves of such extra articles of clothing as might interfere with our transit through the galleries, or render our subterranean sojourn uncomfortable in consequence of the excessive heat, which, in some portions of the cave, is almost intolerable.

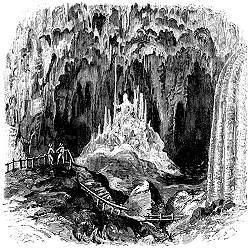

From this elevated natural terrace we obtain our first grand view of the interior. It is like standing in the gallery of a temple. This first hall is about five hundred feet in length, with an average width of two hundred, and an elevation from the abyss to the dome of about one hundred. A number of large lamps have been so placed that the whole interior can be taken in at a glance. At the farthest extremity of this chamber are two dark spots. These are the entrances to two of the principal avenues, which, after continuing for some distance, intersect each other, so that we can pass out of the main hall at one of the dark spots and return into it by the other. At the apex of this irregular V another avenue starts, which penetrates still deeper into the earth, altering the V into a Y, the base of which is nearly a mile from the entrance under the pavilion. The general course of these avenues is east. Starting also from the main hall is another principal avenue, running south for a distance of three miles, according to the measurement made by Mr. Santos Parga. A third avenue penetrates under the hill in a westerly direction for a distance of a mile, diverging also from the main hall, or "Gothic Temple," as it is named.

As we step upon the terrace the first object that strikes us is one calculated to make an impression not soon to be forgotten. It is a cluster of tall stalagmites standing directly in the centre of the chamber. We do not need the hint from the guide to the effect that this is called the "Guardian of the Temple;" we see that at once for ourselves. It is the colossal statue of a warrior seated upon a sort of Gothic throne; in his right hand he holds uplifted a tall, keen lance; his left arm is bent, and rests upon his thigh; his head is slightly turned, as if toward the opening by which we have just entered; he stares us in the face, and, as the yellow and unnatural light of the lamps flickers about his vague features, we can easily imagine that we feel the fixed and freezing glare of his stony eyes. We are forcibly reminded of some tale of enchantment read in our childhood, and we can not divest ourselves of the singular fascination which this weird and supernatural figure exercises over us. Our curiosity compels us to seek a nearer view of this stern, motionless, eternal sentinel, placed there by nature to watch over the hidden treasures of this shadowy domain. Accordingly we descend into the dark gulf at our feet, along a zigzag path cut in the gravely and crystallized soil of the terrace, and approach the spot where we but a moment since saw the giant form of the warrior gnome. Alas! we seek for it in vain; it is nowhere to be seen, having melted away as though at another touch of the enchanter’s wand. What we behold in its place is but a confused heap of broken stalagmites, without any discoverable shape or meaning. The delusion is complete.

From the foot of the terrace we look up at the lofty dome overhead, encrusted with sparkling crystallizations which dazzle us, and gaze down from the little bridge on which we stand, and which spans a deep and perilous ravine, into the darkness. We can not escape a sort of vague terror. Indeed, we feel here as trespassers upon a forbidden precinct; and as if there were a fifth element - darkness - which we have rashly entered.

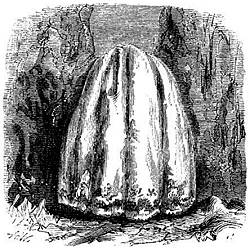

Among the pillars of the temple, which look as if they were sustaining the weight of’ the lofty arches, there is one remarkable for its large proportions; it is called the "Mantle of Columns," owing to the deep flutings in its surface, which bear some resemblance to the drooping folds of a mantle. Here the stalactites and the stalagmites, the former growing downward and the latter upward, have met and formed one solid mass of crystallization about sixty feet in height and twenty feet in thickness, as white as snow and as transparent as alabaster. As we wander through the grotesque aisles of this gorgeous cathedral every thing around us sparkles with brilliant concretions that dazzle the eye.

Whatever advantage, as to extent, other caves may possess over Bellamar, surely none in the world can surpass its wondrous wealth of rare and exquisitely beautiful crystallizations. Nature seems to have exhausted her fancy in producing these myriads of quaint forms and curious combinations. The stalactites are singularly capricious and beautiful.

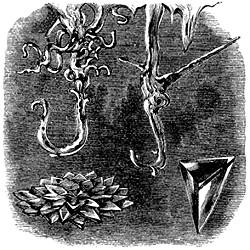

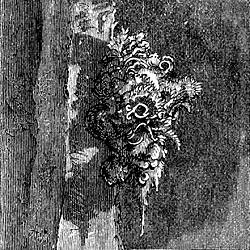

From the gigantic "Mantle of Columbus" to the newly formed delicate tubes and cones, scarcely an inch in length, there exists every intermediate variety of size. Some are flat and transparent, and will vibrate when struck, with a sound as clear and melodious as a silver bell. Others are tube-like, hollow, twisted, or curved, sometimes branching like coral, as others hanging like hooks, or darting sharply upward. According to the accidents of their position, they assume at times entirely different forms. Now they are frozen driblets along the yellow surface of the rock; again they have worked themselves into grotesque fringes, or are scalloped into delicate frills; now they are like glittering serpents flashing wildly in the torch light; then the rock is coated as if with a heavy frost; and again, the shapes take the form of crucibles, of cornucopia, or of flowers tinged with delicate colors and resembling dahlias and roses.

In the complex web which they form it is difficult at times to separate the stalactites from the stalagmites. The latter form, in some places, rich curtains of the whitest and most quaintly patterned lace they hang like the rich drapery of silken robes; or, like motionless cascades of glittering diamonds, they extend, wave after wave, and fold after fold, from the ceiling to the floor. Sometimes they assume the most grotesque forms and resemblance’s; here and there we see them about the floor like devotees kneeling before fantastic idols, in silent and eternal adoration; again they seem like weary travellers stretched out to rest at noon on the cool grass by the wayside; or, perhaps again, like plumed and naked savages gathered in dread circles around the council fire to plot the warpath, or to plan the chase.

And all this is accomplished simply by the combination of water with lime! A feeble stream of water permeates the limestone above, and filters through it, carrying along some minute particles of lime in solution. As this water drops from the roof of the cave, or dribbles along the surface of its walls, it leaves behind it these calcareous particles, which, in the form of carbonate of lime, harden and are crystallized, forming a thousand capricious figures. If the drops fall from the roof, the form is generally that of a pendent tube, or elongated cone, terminating in a keen point, to which every additional drop from above naturally runs. Each drop remains there suspended for a moment, contributing its infinitesimal quota of lime toward the lengthening of the stalactite downward; it then falls to the ground, carrying with it the residue of the line, which is there deposited and crystallizes, contributing to the growth of the stalagmite upward. Thus every drop tends to increase the two formations.

If the driblet of water, however, flows along the surface of a rock, then it leaves the lime behind it to mark its devious path in the form of delicate tracery and fringes. If the quantity of water is large, then the cascades and curtains and snow-drifts are formed. The roof of the cave, its walls, and its floor, are thus all, at the same time, being ornamented through the agency above described. Considering the extreme slowness of the process, how many ages it must have required to agglomerate gigantic masses of crystallization like that called the "Mantle of Columbus!" And yet this, necessarily, is not so old as the cave itself.

Caves such as Bellamar are to he met with on a smaller scale in all the calcareous formations on the island, where natural bridges, tunnels, and subterranean rivers are likewise found. The origin of the Cave of Bellamar may be due to volcanic action; but it is more probably owing to the gradual erosion of yielding strata by the action of water. The wonderful tunnel bored by the Cuzco River, in the eastern part of the island, might suggest the origin of a cave like this of Bellamar. The Cuzco is an insignificant and shallow stream, which, however, in the rainy season, becomes a powerful torrent. A lofty ridge barred the course of its ancient channel, and through the heart of this ridge it has carved a tunnel large enough to admit of the passage of huge trunks of palms and rhododendrons. After disappearing at the base of the hill, several hundred feet below the crest, it does not appear again until it comes out at the other side of the ridge, a distance of nearly three miles. Any volcanic action tending to alter the level or bed of the stream might divert its waters into a different channel; the former one would be soon covered with a dense vegetation, and all distinct traces of it be lost. The tunnel, or cavern, itself probably disturbed from its original horizontal position, would remain to puzzle future geologists.

The Cave of Bellamar, however, has no known communication with the upper air except by means of the artificial entrance broken through the thin earth which roofs over the principal hall, or "Gothic Temple," and its avenues, as far as explored, have all a downward grade, sinking to the depth of four hundred feet below the surface of the hill.

Passing the "Guardian of the Temple," we will visit what is called the "Altar." It stands in a spacious niche at the other side of the chamber, and facing the "Mantle of Columbus." It is a rude imitation of an altar, around which one may imagine that he can discover the forms of sculptured images, animals, and flowers.

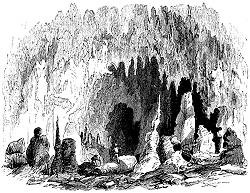

We next follow the guide into the low subterranean passages, entering at the dark spot on the left, into what is called the "Avenue of the Fountain." This avenue is about half a mile in length, and presents at every step objects curious and beautiful; here you have on one side fantastic arabesques sculptured in relief on the dusky walls, quaint Gothic friezes and cornices, and Norman pillars; on the other side is a miniature polar scene, with its icebergs and piled snow-drifts and icicles ; beyond we stop to notice the exquisite embroidery on a cambric robe, or the delicate tracery on a half-drawn curtain; then we come to a portion of the passage which, as it narrows, becomes so low that we must stoop to avoid the long stalactites which hang from the roof; then we creep carefully along the brink of some deep gullies and ravines which look like new dug graves, where all is sepulchral and dark and dismal. Suddenly we find the passage has widened into a beautiful chamber, radiant with crystallizations, which make it seem as if we had passed from the night into the day.

Here is the fountain or spring from which the avenue takes its name. It wells up near the middle of the passage. It is a clear and sparkling fountain, gurgling in a polished vase of sculptured alabaster.

We are now at the apex of the V. On our left is a dark and irregular opening. This is the entrance into the passage through which, by-and-by, as we return, we shall again enter the "Gothic Temple." Picking our way cautiously among the debris of fractured stalagmites we soon reach a gloomy archway and recess called the "Devil’s Gorge." Any lugubrious machinations suggested by this name, however, are rapidly dispelled by the sight of a monster church organ, with its pipes quite symmetrically and elegantly arranged, and its row of ivory keys, which seem only to need the touch of some enchanted hand to fill those dark corridors, those gloomy depths, and lofty vaults, with the swelling and sonorous strains of a solemn music not meant to be listened to by mortal ears.

Not far from the organ there is another object which carries us pleasantly back to the familiar world of irrepressible realities: it is a rare and beautiful stalagmite, broad, smooth, thin, and very transparent, with perpendicular folds and plaits, and tastefully embroidered along the base with rich and graceful patterns. This is called the "Embroidered Petticoat." In order to show the embroidery to advantage, a light is placed behind it, when the exceeding transparency of the stalagmite sets off the denser lines of the patterns to greater advantage. Beside this memento of the upper world there is, just beyond, an elegant sofa, covered with white damask, with its curiously wrought back of silver and of ivory, and its rich and glossy cushions, which, though not so soft as they look, yet silently invite the beholder to the dreamy luxury of an Oriental siesta. This luxury, however, we must endeavour to forego, because there yet remains a great deal to be seen, and the guides, who are all day long breathing this cavernous atmosphere, and are constantly being taught how much has been successfully accomplished by the restless and persevering labor of ages, will not fail to remind us that to them also, in this dark world of subterranean speculation, "time is money."

So we take another lingering look at the wonders of the "Devil’s Gorge," and, with a parting sigh for the damask sofa, we again follow the guide, and plunge still deeper into the cavern in search of other wonders.

After continuing along the avenue for a short distance we come to a contricted and rugged passage, where we have to stoop low to avoid a savage-looking boar’s head, with keen and desperate tusks, that menace us from the low roof, and immediately beyond we suddenly find ourselves in one of the most beautiful chambers of the cave. It is called the "Chamber of the Benediction," because it has been rendered historical that here a certain Catholic bishop, who had come to visit the cave, was so enchanted with the beauties he beheld, that, in the exuberance of his pious admiration for the wonders of the created world, he blessed and consecrated the Cave of Bellamar.

This splendid hall is nearly forty feet from the floor to the roof: it is somewhat more than that in length, and has a breadth varying from twenty to twenty-five feet. The extreme beauty of its crystallizations, with their spotless whiteness and brilliancy, its graceful columns, and the smooth and even floor, all render it a favourite with visitors.

On the right, as we enter, there is a running spring which overflows into a shallow basin, whose pure waters are seen to glisten among numberless stalagmites. This shallow basin is in a low recess under a massive frieze-work, highly ornamented, and the receding portions of which are seen beautifully reflected on the tranquil surface. Upon approaching the spring we stoop and look into the recess, and perceive that there is at the back of it a dark opening, through which comes the streamlet like a silver thread. That dark aperture is the mouth of an extensive passage, which has been explored for the distance of nearly a mile by Mr. Parga and two others. When at that distance from the mouth a jet of water from the roof extinguished their only remaining taper. They attempted to light some matches with which they had provided themselves, but these had been rendered useless by the dampness, and one after another failed until only one was left. This was their last hope. They felt it would be impossible, in the dark, to retrace their steps through the labyrinth of narrow and tortuous passages, and the dangerous places they had passed. They groped about, feeling with their hands for a dry spot on the surface of the rocks. The last match was finally tried; it flickered for an instant, and went out! The situation of the explorers was now very critical. Weary as they were-for they had been wandering all day through those intricate passages-they were now compelled to creep on their hands and knees, the sharp stalagmites tearing their clothing and lacerating their limbs. At moments they would sit down to rest themselves, exhausted and despairing, in this horrible darkness. It was midnight, and they seemed to he no nearer to the mouth of the passage than they had been in the afternoon when their light was extinguished. As death was staring them in the face, after hours passed away, and as they groped about those dark passages, which brought to their ears only the useless echoes of their own voices, the perils of their situation every moment more and more apparent, their terrors increased as hope grew less.

At last, toward morning, one of them thought he heard the echoes of other voices. They listened with breathless anxiety; a calmness and silence as profound as that of the grave seemed to mock their hopes.

Suddenly there came, faint and distant, the reverberation of a voice. They replied, and it answered them again. They pushed on toward this voice, groping in the darkness. The two voices sought each other. Soon a distant glimmer, like that of a faint star shone in the distance. It came nearer and nearer.

The wife of Mr. Parga, alarmed at his long absence, had persuaded some friends to go into the cave in search of him. They were in this way rescued from a fearful doom.

This basin, with its crystal waters and its cool atmosphere, has a delightful effect upon the mind of the visitor. But the guide’s narrative is not calculated to produce an equally agreeable result. We are never entirely at our ease when underground. The close, hot air of these caves suffocates us; the silent darkness ahead is terrible; the brain reels; there is at moments an irrepressible longing for the open air; the voices of our companions sound weird and unnatural, and the red glare of the tapers has something demoniac in it. We are startled at every slight noise behind us; a sort of vague terror haunts us lest the lights may go out, or may not last until we regain the entrance; or the ponderous dome give way, and, looking up the narrow aperture which is our only means of exit, may consign us to the frightful doom of being buried alive in this natural sepulchre!

Near the spring is a beautiful piece of crystallization called the "Mantle of the Virgin." The crystals which adorn it are of extraordinary size and brilliancy. It looks like a mantle of white satin, embroidered with silver thread, and ornamented with diamonds and pearls.

The vaulted roof of this beautiful chamber is hung, in some parts, with innumerable stalactites of all shapes and sizes, the most of them presenting the appearance of alabaster lamps hung from the ceiling. As the guide waves his torch over his head, each one of these lamps darts forth a thousand brilliant concretions in splendid rays of azure, gold, and crimson. They are fairy lanterns, each lit with the haze of a burning diamond. Among these stalactites there is one deserving of special notice. We reach it by passing through a narrow and irregular passage called the "London Tunnel." This stalactite is an exquisite specimen of subterranean workmanship. It has been named "Don Cosme’s Lamp," from the fact that a Havanese gentleman of that name offered to pay a thousand dollars for it, provided he was allowed to carry it home with him entire. It is a yard and a half in length, quite broad at the top where it is joined to the roof and terminates below in a keen point. It is a perfect specimen of its kind, and is covered with brilliant crystallizations, and fancifully decorated with the most delicate filigree work, tinted with violet and pale gold. The myriads of minute branching stalagmites on its surface are twisted and woven about each other in the most capricious and complex shapes. Indeed this portion of the cave can not be surpassed for the beauty and quantity of its crystalizations. The roof and walls are literally encrusted with them. It will, perhaps, be our good fortune to notice a curious and beautiful representation of a rainbow on one part of the wall, in which, on a dark ground, the colors of the solar spectrum are accurately displayed in a semicircular form. As a torch is moved back and forth before it the effect is beautiful beyond description. Here, too, the ceiling is, in many parts, of a rare delicate salmon-color, studded with myriads of brilliants; and graceful colonnades of stalactites, solid to the floor, fall into varied perspective as you move about the chamber, giving to the whole the appearance of some enchanting Oriental retreat.

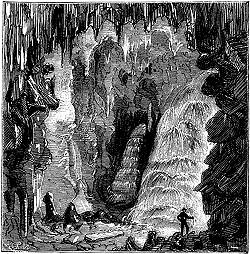

We pass out of the "Blessed Chamber" and its lovely grottoes and quaint recesses with no little regret, and follow the guide along the last portion of the main corridor into what is known as the "Avenue of the Lake." On our way we pass many beautiful and interesting objects, but we have seen so much, and our eyes so acne with prying and staring, that we stop only for an instant to contemplate the beauties of a dazzling waterfall called the "Diamond Cascade" - a glowing mass of crystallization, which looks for all the world as though some princely gnome, standing in a niche which is near the roof, had emptied down a casket of diamonds, which, in a glittering shower, had remained suspended in the air.

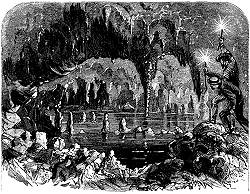

But we hasten on to obtain a view of the greatest wonder of the cave - the "Lake of the Dahlias," which is at the termination of the avenue. We are now at the bottom or foot of the Y, and somewhat less than a mile from the pavilion. In order to reach the lake it is necessary to climb up to an aperture near the roof, above the smooth surface of a rock coated with a cascade of crystals, which looks as if it might be an overflow of the waters of the pool. As we approach this end of the gallery we observe a marked change in the temperature of the air, which gently fans our temples with a delicious coolness. This is a breeze from the lake-a beautiful sheet of water, one hundred and eighty feet long, thirty feet broad, and eighteen feet deep. It is pure and transparent, and its bed or bottom is paved with the most remarkable crystallizations, most of them of the shape of flowers resembling dahlias. These dahlias are formed by triangular, concave crystals, starting from a common centre, in layers one above the other, precisely as the petals of dahlias are arranged. They vary from three to five inches in diameter. Their greatest beauty consists in the exquisite manner in which they are tinted with veins of violet and blue and delicate yellow and pale crimson. These colors are probably due to the presence of mineral salts which filter down with the water from the overlying strata. The dahlias are all slightly flattened, as if by the pressure of the fluid above them.

Here, then, we have an enchanted lake in which the most fastidious of naiads would not refuse to dwell. A lake with its surrounding landscape of fantastic, sparry forms and its beds of wondrous flowers, and with its own sky bending above it full of sparkling constellations - a lake on which the sun has never shone, and whose smooth and silver surface the light wings of the breeze have never rippled, nor the rage of the tempest ever maddened into foam.

Retracing our steps we now return to the fountain, where the avenue of that name is intersected by the passage which, in conjunction with it, forms the V. This passage is called the "Avenue of Hatuey" - in memory of the Indian chieftain whose martyrdom is recorded in the early annals of Cuban history. After proceeding along this passage for a short distance we come to a spacious vault called the "Cupola of St. Peters," from the symmetrical proportions and great elevation of its dome. Directly under this dome stands isolated a tall, keen stalagmite called the "Lance of Hatuey."

As we continue to explore this passage our attention is constantly directed to the great variety of rare fossils embedded in the walls and roof. The latter consists here of a stratum of yellowish conglomerate. Among other remains are casts of oyster shells, some of which measure six inches in length, with a proportionate width. There are also casts of echini or sea-urchins, some of them measuring as much as seven inches in diameter. The existing species of oysters found in the island are seldom more than two inches in length, being generally found adhering in clusters to the tangled roots of the mangrove-trees along the sea-coast, in the same manner as Columbus, in his fourth voyage, said he saw them along the shores of South America. The sea-urchins found at present on the island are seldom more than three or four inches in diameter. These casts carry us back to a remote era.

The "Avenue of Hatuey" is rendered very picturesque by the tortuousness of its course and the inequalities of its floor. In some places we descend into deep ravines, to ascend again along erratic zigzag paths; in some parts it is necessary to stoop quite to the ground to be able to creep through the narrower passes. There abound many beautiful encrustation’s, especially those veins with colors-buff, red, and blue. Some of the colored stalactites are very striking, especially near a beautiful recess called the "Boudoir of the Matadzas Beauties." It is a very beautiful chamber, with arches and pillars tastefully distributed and decorated. A quaint Gothic niche near by also displays the usual wealth of rich ornament and tracery, and fanciful design. It reaches from the floor to the ceiling, but is roofed over at the height of about six feet; a broad, flat stalactite serving as a partition wall and leaving a narrow doorway. In this wall is a small Gothic-shaped opening, or window. We need not be told the name given to this eccentric little nook is the "Confessional."

We have now to toil for some distance over the fatiguing irregularities of the narrow path which leads us up a very steep ascent to a terrace which is on a level with the floor of the "Gothic Temple." We have then returned to our starting-point.

Most of the other galleries are not as yet opened to visitors; it is hoped that before long they will be rendered safe enough to be exhibited, as they are said to contain many interesting and wonderful objects. But we have seen enough for one visit; we have spent a whole morning in these realms of subterranean mystery, and as we climb up the stairway to the pavilion and behold again the clear, white light of heaven, and breathe once mere the pure untainted air of the outer world, we can not but confess that we feel in the best of spirits-a vein of good-humour with which is pleasantly blended that wholesome excitement we always experience after the contemplation of the marvels of nature, even when our investigation has been associated with a sense of peril.

- See also

Cuevas de Bellamar

Cuevas de Bellamar Cuba

Cuba

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps Search

Search