Caves in Crystalline Rocks

Today the terms basement or crystalline basement are not very popular anymore, the terms are somewhat out of fashion. They were introduced by the theories of the 19th century and were replaced by the terminology of modern plate tectonics. For our purposes, however, this term summarizes quite well the multitude of insoluble rocks, which are thus not subject to karstification. All continents have a core of very old crust consisting mainly of metamorphites and intrusive rocks. They are very often so-called inactive orogens, i.e. mountains whose formation has ended, which have since been overlaid by younger sedimentary rocks. We call them shield or craton and they are generally quite big. Smaller areas of basement may be formed as uplifted fault blocks whose sedimentary cover has been eroded as a result of the uplift.

What interests us here is not so much the geological genesis of the rock, its the potential for cave formation. Since those rocks are not soluble, karstification is not possible. On the other hand, all cave formation processes based on mechanical weathering are possible in any kind of rocks. We find few caves and these are then often small-scale, formed by wind erosion, water erosion (river caves and sea caves) as well as the whole palette of the tectonic caves. And, in a small scale, metamorphic limestone aka marble may allow karst caves, but those marble areas are in general quite small.

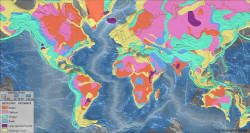

If you look at the major geological regions of the Earth’s crust on the map, you can easily see the cratons marked in orange. This also makes clear that large parts of Scandinavia, Africa, Canada and Greenland have no soluble rocks and thus very few caves.

Search DuckDuckGo for "Caves in Crystalline Rocks"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Caves in Crystalline Rocks" Basement (geology) - Wikipedia (visited: 04-AUG-2021)

Basement (geology) - Wikipedia (visited: 04-AUG-2021)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps