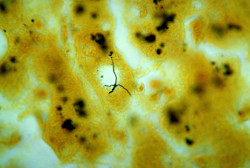

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is an infection with Leptospira bacteria, causing flu-like symptoms, fever, chills, muscle pains, and intense headache. There are cases where the patient has no symptoms at all, but about 10% of all cases are of the severe form called Weil’s disease, because it was first described by Adolf Weil in 1886. After an incubation period of 2 to 20 days the first phase with above mentioned flu-like symptoms starts. After a few days the patient gets better, but after another three days the second phase causes meningitis, liver damage (causing jaundice), and renal failure. If untreated the severe form takes about 30 days and has a death rate of about 30%.

The problem with leptospirosis is, that it is often wrongly diagnosed because of its unspecific symptoms. And it is extremely rare, with annual infection rates of 0.02 per 100,000 in temperate climates. So it is unknown to most doctors. This may result in wrong and/or too late medication. It is much more common in tropical climates with annual infection rates of 10 to 100 per 100,000.

Leptospirosis is transmitted from animals to humans by water contaminated with urine of infected animals. Infections enter the body after prolonged immersion in water, through small wounds or scratches and through eyes, nose or by swallowing the water. While urine in water is the most common way of infection, it is also possible with any other body fluid, including semen and blood. Special occupations are at a much higher risk, including veterinarians, slaughterhouse workers, farmers, and sewer workers.

The connection between Leptospirosis and caves is simple. If there are millions of bats roosting in a tropical cave, the urine is falling down into the cave river. As a result, even if only a few animals are infected, the water of the cave river is highly contaminated. Cavers wade through the water for a long time, one way for the infection to enter the body. Bruises are also common during caving. An infection is very likely, even if the caver is very careful.

For adventure travellers to high risk areas prophylaxis with 200–250mg doxycycline once a week is recommend. But a few years ago the case of a caver who returned from caving in Sarawak was published. He became infected despite taking doxycycline daily for malaria prophylaxis. Caving in tropical zones increases the exposure risk due to the combination of possible multiple skin abrasions in combination with hours of immersions. The water in caves may also increase infection risk because of increased water pH. As a result even standard prophylaxis may be inadequate.

We have listed several cave trekking ventures in tropic countries on showcaves.com. Some include wading through underground rivers and mention the interesting bat colony in the cave. While we generally do not want to tell you, this was extremely dangerous, we suggest you be aware of the possible dangers. Prophylaxis is a good idea, if you show symptoms afterwards, be sure to tell your doctor where you went caving, so it is possible to determine the kind of infection with a test and take the right measures. If properly medicated the disease is more or less harmless.

Literature

- David A. Haake, Paul N. Levett (2015): Leptospirosis in Humans, Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015; 387: 65–97. online DOI

- A.M. Monahan, I.S. Miller, J.E. Nally (2009): Leptospirosis: risks during recreational activities, Journal of Applied Microbiology 107(2009) 707–716, ISSN 1364-5072. pdf DOI

- See also

Search DuckDuckGo for "Leptospirosis"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Leptospirosis" Leptospirosis - Wikipedia (visited: 30-JUL-2011)

Leptospirosis - Wikipedia (visited: 30-JUL-2011) Leptospirosis Information Center (visited: 30-JUL-2011)

Leptospirosis Information Center (visited: 30-JUL-2011) Leptospirosis at the CDC (visited: 05-APR-2020)

Leptospirosis at the CDC (visited: 05-APR-2020) The boys rescued from the cave in Thailand could have been exposed to dangerous infections from bats, fungus, or water (visited: 05-APR-2020)

The boys rescued from the cave in Thailand could have been exposed to dangerous infections from bats, fungus, or water (visited: 05-APR-2020)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps